- Home

- Gabino Iglesias

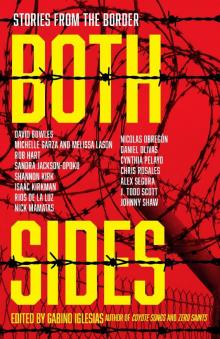

Both Sides

Both Sides Read online

BOTH SIDES

Stories from the Border

Edited by Gabino Iglesias

The following is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, events and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or used in an entirely fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2020

Introduction — Gabino Iglesias

The Letters — Rios de la Luz

Los Otros Coyotes — Daniel A. Olivas

Fundido — Johnny Shaw

American Figurehead — Shannon Kirk

Colibrí — Nicolás Obregón

Buitre — Michelle Garza and Melissa Lason

The Lament of the Vejigante — Cynthia Pelayo

Fat Tuesday — Christopher David Rosales

The Other Foot — Rob Hart

Waw Kiwulik — J. Todd Scott

El Sombrerón — David Bowles

She Loved Trouble — Sandra Jackson-Opoku

Grotesque Cabaret — Isaac Kirkman

Empire — Nick Mamatas

90 Miles — Alex Segura

Cover and jacket design by 2Faced Design

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-947993-87-7

eISBN: 978-1-951709-12-9

Library of Congress Catalog Number: tk

First hardcover publication: April 2020 by Agora Books

An imprint of Polis Books, LLC

221 River Street, 9th Fl., #9070

Hoboken, NJ 07030

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction — Gabino Iglesias • Page 7

The Letters — Rios de la Luz • Page 10

Los Otros Coyotes — Daniel A. Olivas • Page 20

Fundido — Johnny Shaw • Page 44

American Figurehead — Shannon Kirk • Page 58

Colibrí — Nicolás Obregón • Page 79

Buitre — Michelle Garza and Melissa Lason • Page 103

The Lament of the Vejigante — Cynthia Pelayo • Page 124

Fat Tuesday — Christopher David Rosales • Page 139

The Other Foot — Rob Hart • Page 154

Waw Kiwulik — J. Todd Scott • Page 164

El Sombrerón — David Bowles • Page 182

She Loved Trouble — Sandra Jackson-Opoku • Page 187

Grotesque Cabaret — Isaac Kirkman • Page 237

Empire — Nick Mamatas • Page 258

90 Miles — Alex Segura • Page 268

THIS IS ABOUT PEOPLE

An Introduction

Gabino Iglesias

My first border was the ocean. It was always there, surrounding me on all sides, dictating the limits of my life. It was an endless blue thing that kept me away from a world I didn’t know. Then I grew up and started realizing how borders are everywhere. I hated all of them.

I grew up and the ocean was still there, blue, eternal, and relentless. Planes helped me break its power over me. Planes shattered an invisible wall and showed me borders were meant to be crossed, to be ignored. I refused to remain landlocked.

Years later, I made peace with the ocean and sat before it regularly. I kissed girls, got drunk, bathed in it. I also sold stolen jewelry in front of that ocean because being poor is also a border, a boundary that keeps you within something you want to break free from.

As the years passed, my name became a border, an unpronounceable amalgamation of vowels that many monolinguals struggled with and butchered. My parents hadn’t gone to college, and their history became a border. My country became a border. My lack of education, my age, and the fact that I didn’t speak English all became borders. My hatred grew. It became a force, an unstoppable weapon.

Borders. Limits. Boundaries. Lines. Confines. Fuck them all.

They are there to be demolished, jumped over, overcome.

In 2008, I moved to the United States. I was naïf and believed education was a surefire way to upward social mobility. It wasn’t. Moving to the United States uncovered more borders. My second-class citizenship became a new border I had ignored before. My accent became a border that affected the way others saw me. My socioeconomic status was a border that kept me living in certain places and wearing certain clothes and stealing toilet paper from work to survive. And you know what? I was lucky. I was lucky because I had a blue passport with an eagle on it. Sure, it wasn’t good enough to make a full citizen or grant me the privilege other enjoyed, but it was good enough to keep me here and not make me fear deportation. Which is luckier than most with my borders.

I won’t bore you with the details of my life in this country. What you need to know is this: my doctoral dissertation was done with DREAMers, I spent a year teaching ESL night classes to undocumented workers in Austin, I worked with an immigration lawyer doing translation, and now teach a public school in East Austin where there are many undocumented kids and even more undocumented parents. I’m an authority on immigration, and everything you think you know about immigration is wrong.

The US-Mexico border has militarized and politicized. It has been turned into a talking point, instead. It’s not; the border is a humanitarian crisis, an open wound, an interstitial space where idiots worked really hard at stopping progress and spend a lot of money and time strangling the American Dream. Well, I believe the most important thing fiction can do is tell the truth, and that truth is crucial right now. The anthology you now hold is a tool that will help us do a little bit of the most significant thing contemporary American fiction can do: rehumanizing la frontera.

I’ve heard that being too political can hurt your book sales. I don’t care. I care about humanity. I care about people. I care about the Haitians who move to the Dominican Republic and the Dominicans who build boats to go to Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans who leave everything behind and move to Florida or New York because we all want to live better lives. I care about every family crossing our border, about every parent fearing for the safety of their child, about every separated family member sending money home, about the tears and the fear and the injustice. I care about the fact that migration is the history of the world, and stopping migration is stopping progress. I care about every writer in this anthology because they care about the same things and are willing to write about them from their perspectives: an angry lawyer, someone who used to work for the carteles and now does water drops in the dessert, a Boricua struggling with her identity, a man who was in the middle of the action as a federal agent fighting Mexican cartel in their smuggling routes. They are all here. They make this a beautiful, incredibly diverse book that looks at the issue of borders and immigration from a plethora of spaces, and enriches the discussion as it illuminates what a lot of people ignore.

Al carajo todas las fronteras.

This anthology is about borders. However, this is a book about people. Why? Because too many forget that people are at the core of every immigration debate. Yeah, this isn’t about borders, this is about the people on both sides—and across—those borders.

Bienvenidos a la frontera.

Gabino Iglesias

December 2019

THE LETTERS

Rios de la Luz

Emiterio and Alonso sprint across the 375 Border Highway. A violet semi-truck with spiked hubcaps wails at the two of them. Alonso’s shoes are falling apart at this point in the journey. They used to light up when he first got them. They were a gift for his seventh birthday. He is almost eight, but he thinks of himself as an old soul. His Bart Simpson socks have holes in the heel and big toe. Rocks and stickers become the cushion in between his small toes. He wears his favorite t-shirt with a dragon and gargoyle battling. He followed his dad because Emiterio was the only person who understands his q

uirks. The way he chews on his tongue when he was nervous. The way he pops his knuckles before he interjects his opinion into an adult conversation. The way he never looks someone in the eye until he becomes comfortable with them. Emiterio is running because he wants to be like the coyote puppies who cross between Texas and Mexico. The ones who howl and scavenge and survive. He is running because he needs to feed his son and his two children who stayed behind with the love of his life. He needs a second chance.

The Sanchez family helps the priest lug in his suitcases filled with Bibles. The priest explains it is better if the family chooses the Bible they want to hear a prayer from. Grandma Lala is dying. Tumors in her stomach erupted and she coughed up blood. Within an hour, she started vomiting blood. Then, it escalated to her begging for an exorcism. Her eldest son, Esteban, looks at the open suitcases on the ground and picks out the Bible with the gold and red striped cover. The words inside are printed in red. An ink drawing of the crucifixion is scribbled on the last page. He hands the Bible to the priest and leads him to the backroom where Lala has slobbered down her chest and is reaching at the ceiling. Moths on the moon. Dirt in my throat. She keeps repeating the words, over and over until she falls back to sleep.

Screaming erupts from the cement front yard. Two Border Patrol agents have a man and a boy pinned to the hood of Esteban’s car. The boy is tiny. Nine at the oldest. Esteban grabs his phone and films the two agents. The boy is crying and gagging as he sobs. The Border Patrol agent slams him into the cement, spits on him, and says, “Better luck next time.”

Emiterio and Alonso are separated. Alonso gets placed in a tent city outside of El Paso. Emiterio gets deported without his son.

Esteban’s video goes viral. The video cycles through the discussions of online scholars, online bigots and news outlets. A month after the replays wind down, both of the Border Patrol agents in the video end up dead. One agent falls head first from the second story of the mall. The other suffers a brain aneurysm while eating breakfast.

Cops have started to show up at Lala’s house. Every single day. Someone waits for Esteban in the front yard. He is mourning. Lala died the night before spring started. As she was going in and out of consciousness, she told Esteban the world was going to end underwater. We will all drown and the earth will devour us.

Esteban went on a cleaning spree and scrubbed every crevice of the house after Lala’s body was taken to the morgue. A cop he doesn’t recognize bangs on the door. Curious to feel out the aggression, Esteban opens the door and extends his yellow dish-gloved hands to greet him. He’s not a cop. His name is Gustavo. Gustavo takes a count of the golden crosses on the living room wall. There are thirty-three total. He looks at the quaint bookshelf filled with self-help books. He asks Esteban if he could take a look around Lala’s house.

“What are you looking for? She just died, man.”

Gustavo bites his tongue and sighs, “I had a dream with Lala in it.”

Esteban steps back and looks for possible physical traits that this man could be related to him. Esteban asks for more details. Gustavo claims something in the house belongs to him. Gustavo’s throat seizes up and he ends the conversation in a coughing fit. Esteban feels the weight of discomfort slamming against his temples. He asks Gustavo to leave. Maybe another time. A small shadow appears behind Esteban and watches Gustavo get into his blue Mustang and drive away.

Three more Border Patrol agents die. Three days apart from each other. The first agent is crushed under a semi as he crosses the street. The second agent slips on a hiking trail in the Guadalupe Mountains and tumbles through the desert until she blacks out and dies minutes later. The third one has a food allergy. His throat closes as he rides up an elevator. Esteban keeps track of the deaths. He reads conspiracy theories online claiming the Border Patrol agents have been taken hostage in other timelines.

Alonso dreams about his family every single night. They travel together. They eat together. Sometimes, he sees them in the distance, he screams for them, but his voice is inaudible. ICE agents whisper about him in English and he understands them, but he knows better than to give himself away. They claim he cursed the agents who took him away from his father.

Alonso spends his nights reading under a table with a flashlight. The boys have made it into a cardboard fort. Alonso has read travel pamphlets, a bible, a book on Greek mythology, and a choose your own adventure thriller inside the fort. The boys take turns sitting inside when they want to be alone.

Alonso convinces every boy in his tent to start a silent protest. They will start in the morning and vow only to say something if someone is in grave danger. Alonso holds little trust for the ICE agents. They always say the same thing: “If you don’t behave, we’ll send you back where you came from.” He doesn’t want to waste his words on them. In the morning, the boys look at each other and pinky promise in a silent shuffle as they go outside for their allotted hour. The sun stings their eyes as they become exposed to the desert. The dry air warps the sun into an oven. The boys step out and look at their feet. There are hundreds of holes in the makeshift soccer field. Alonso reaches inside and pulls out a letter from beneath the earth. The dirt smells fresh. The envelope has gold trim around the edges and a name written in red ink on the front. He slips the envelope into his pants. Alonso looks around and gestures to another boy. He hands an envelope over to him and then motions for the other boys to dig. One by one, they find envelopes and hide them.

After their play hour is over, Alonso opens the envelope labeled “Elena Villalobos.” The letter tells her birth story. She was born in the morning on a blustery day. The winds knocked power lines over throughout the city and mourning doves attacked people with blonde hair with no explanation. The letter stated she was to die the next morning. Alonso’s heart raced. As he read each word, they disappeared. He collected the envelopes and read them carefully inside the makeshift cardboard fort they were allowed to build. Name after name, he vowed to stay silent.

Then, he recognized one of the names. Ricardo Quevedo, an ICE agent who punished the boys by hitting the backs of their legs with a wooden meter stick. His other favorite punishment was making them sleep in a dog kennel if they didn’t listen to his instructions when they were lining up to eat dinner. He was fired because of a DUI. The kids called him Alacrán and tried their best to protect each other from receiving his punishments while he worked at the camp. Alonso could picture the satisfaction on the Alacrán’s face when the boys looked up at him in fear. The name alone filled Alonso with dread. The letters went into no details of their deaths, only the day of their conception. Ricardo was born in Lawton, Oklahoma on a muggy day during tornado season. Like Elena, he was sentenced to die the next morning. Alonso felt his guts tighten. He memorized each name and recited them one by one, not knowing how he was to keep track of whether or not the letters were factual.

When the agents dig into the holes overtaking the soccer field, all they find are fire ants and burrowing owls.

Esteban dreams about Lala. She’s in a red gown with a train so long, he can see it ribboning around the mountains. Lala is cutting into meat and bone with a machete. Over and over until a small creature emerges. It’s a coyote pup who starts to howl as soon as it opens its eyes. With her claws, Lala starts to dig at the cement in the backyard. The cement turns to ash as she digs further down. She digs into a room filled with stacks of books. The puppy follows behind as she pulls out a book filled with names. The language is symbols and formulas. Esteban wakes up before Lala explains what the codex means.

Alonso waits to hear news of any deaths in the campsite. One ICE agent had a heart attack after posting a selfie of herself in her uniform. Another choked on his vomit after binge drinking with his friends. Alonso had listened for the whispers of their names. Both of them were named in the letters. Alonso’s anxiety torments him. He questions if his memorization of each name started the cycle of deaths. He starts to loath being in the tent, but isn’t ready to f

ess up to being some kind of death magician. One morning, the holes in the soccer field fill up with flower petals. Roses, lilies, and orchids. The boys take turns sniffing the petals. Some of the fragrances smell like nostalgia. Alonso pictures his mother receiving roses from his dad and cries so hard it hurts his chest. One of his tent mates holds him and lets him melt into more tears.

It has to do with Lala’s ghost. Esteban has convinced himself Lala has something to do with the surge of deaths.

Lala shows up in Esteban’s dreams again. This time, she’s younger, her hair is long and black and curls cover her shoulders. In a black pantsuit, she’s standing at the gate of a pool. Lala’s tongue is black. She scratches at her tongue and spits dribble into the stale water at her feet. The residue trickles into the pool. Swirls of black and purple oil infest the pool. She chugs liquid from a goblet and eyes the two kids who show up. A young girl in a pink polka dot bathing suit and a boy in dinosaur swim trunks. They hang around the ledge and doggie paddle together in giggle fits. Clouds grey the sky and the pool water becomes darker. The bottom of the pool disappears. A midnight blue. The water erupts. Stingrays jump in and out of the water. The girl and boy continue to play. The girl steps out of the pool and sprints around the ledge of the pool. In a matter of seconds she trips over her feet and thrashes into the water. Waves take the girl under and Lala can’t move. The gate begins to grow so tall, it can’t be seen past the clouds. Lala watches as the young girl floats up lifeless after the water calms down. The young boy tries to save her, but he flounders around until the waves shove him against the gate.

Both Sides

Both Sides Hungry Darkness: A Deep Sea Thriller

Hungry Darkness: A Deep Sea Thriller Gutmouth

Gutmouth Zero Saints

Zero Saints