- Home

- Gabino Iglesias

Zero Saints Page 3

Zero Saints Read online

Page 3

As you approach, a sound comes from the space behind the two dumpsters. You take three steps to the side and look. The kitchen’s manager, a fat gringo named Collin who speaks horrible Spanish and sports a ridiculous mustache, is pressing Sara, one of the counter girls, against the wall. She’s whimpering. He smiles at you and then tells you to fuck off, beaner.

Collin’s head bounces off the wall with a loud crack. Your boot sets his jaw at a weird angle. That causes the second crack. A kick to the ribs only brings a loud exhalation. You imagine a dying buffalo and kick him again. And again. Sara screams at you. Tiene dos hijos. Su marido está preso. No tiene papeles. Este es el único trabajo que ha podido conseguir. She walks over to you and pushes you away from the piece of shit on the ground.

You drop the key on Collin and then get rid of your apron and do the same. You walk out of that filthy alley without entering the kitchen again and never go back to that place.

Julio comes around the next day and tells you to get in the car. You’re going to meet a man about a job, but this is the last time he’s helping you out. He sounds pissed. You don’t explain yourself.

Julio tells you he talked to Silvio and your uncle told him to let you fend for yourself if you want to play hero. Eventually Julio pulls up in front of a house and tells you to knock on the door and say you still smell like the river and want to make some money. That’s when you meet Guillermo. That’s probably the thing that, more than anything, led to the pulsating egg in your skull. He’s the man you have a message for, the man Indio kept calling “el gordo.”

Now you drive as the sky starts turning orange. Every feeling in the world is inside you, but none of them stay put long enough to be identified and dealt with. You need to stop shaking. You need to pop some pills and sleep for half a day. You need to get the images of a beheading out of your skull. But you can’t. You keep seeing the blood flowing out of Nestor’s neck, his face scrunching up. You keep seeing Indio’s arm moving the knife back and forth. You keep hearing the crack of Nestor’s neck once Indio reached his spine and smacked his head to the side. You keep hearing the fucking impossible crunch coming from the bucket.

Around you, the streets seem to have taken on a new kind of darkness, one that has nothing to do with it being night or the lack of stars. You try to concentrate on driving, on moving away from what you saw and toward home and, as soon as the sun rises, a chat with Guillermo, who suddenly strikes you as the only man in the world who can help you fix this new problem you only think you understand.

You get home and walk straight to the Santa Muerte in the little table in the living room. She looks back at you with empty eye sockets that hold all the darkness in the world. You feel better. Nothing will come to get you while you’re next to her. You take some pills and walk back to the statue. The sofa is closer to her than the bed, so you lie down on it and think about disappearing.

3

Laws of physics

Emotional hurricanes – UFO movies

Menudo – Pozole – Tamales

La limpia

Two objects can’t occupy the same space at the same, but feelings are different. That’s the important part. That’s what Lauryn Hill didn’t tell you. That’s what I was trying to get under control that morning. I was angry and scared and felt lonely and wanted revenge and wanted to move elsewhere and wished that everything had been a nightmare and prayed to Santa Muerte for protection and missed my home, my mom, and my friends.

Two oxies are the best way to kill emotional hurricanes.

After taking the pills, I took a long shower. The oxys were working fast. The edges were turning round, and the crippling darkness in my brain started to recede.

I got out of the shower and dressed. Finally, I stepped out of the house into a glare so bright it reminded me of UFO movies and closed the door behind me.

Then I heard my name.

Every muscle in my body tensed. Fear and recognition jockeyed for position inside me, crushing everything else in the process.

I turned around expecting to find a guy with a gun. Instead, I found Yolanda.

The sun haloed her afro from behind. Her café con leche skin made me wish I’d known more words just so I could describe it. As always, her face was makeup-free. Ella le deja eso de la pintura a los payasos. She seemed to be allergic to sleeves. A huge sunflower blossomed on her left shoulder.

“How’s it going? You okay? You look like you had a rough night.”

I smiled at her. Oxy makes smiling easier.

My brain was telling me to take a few steps forward, hug her, and lose myself in her smell. A different part of me wanted to fuck her to death and then greedily suck the marrow from her bones.

“Yeah, I’m good. How you doing?”

“You sure about that? You look a little pale.”

“Rough night. Don’t worry about it. What are you up to today?”

She turned to the side and stuck her key in the door. Her ass was jacked up by killer high heels.

“I’m done with school for the day, so I’m just gonna take a nap and watch something on Netflix. You?”

I wanted to reply to her, but all I could think about was lying down so she could stick one of her heels into my heart and put an end to my misery. How do you tell a woman you like that you’re a fucking coward? How do you explain that some bad men scared you last night and that you’re on your way to see a fat bastard who you hope will take care of the problem quickly so you can sleep soundly? The answer is you don’t. Everyone talks a big game about honesty, but that’s a rare thing. Most people aren’t honest with themselves, so they can’t be honest with others. At least I’m honest with myself. I know I’m a coward. I have no problem with that. I like running away from shit and staying alive. Sue me. That was the truth, but that was not what I was about to say to a gorgeous mulata who was looking at me with her head tilted to the side and half a smile on her face that was hot enough to melt steel.

“I have to go talk to my boss. Nothing important. What are you gonna watch?”

“Problems at the club last night? My friend Juliet loves that place. Maybe you’ve seen her. She’s about my height, purple hair…”

“A few hundred girls walk into the bar every night, and at least half of them have purple, blue, green or pink hair. Tell your friend to talk to me next time she’s in there. I’ll tell Martin to hook her up with some free drinks.”

“Oh, yeah?”

“Yeah, and you should come with her.”

“You know I don’t drink.”

“I’ll get you some apple juice.”

She looked down at her keys. I knew the conversation was over. A part of me wanted to say something, anything, to keep it going. This was not going to lead to anything, but talking to her kept me mellow and made the bad stuff recede into a dark corner of my brain.

“Alright, I’m gonna take that nap. I’ll catch you later.”

“Have a good one, Yoli.”

She walked into her apartment and closed the door. I walked to my car and got in. Suddenly the idea of explaining everything to Guillermo scared me. The man was more likely to ignore everything than to move a finger in my defense. Still, knowing that Consuelo would be there was enough to make me stab the key into the ignition and crank my old pedazo de basura to life.

Consuelo lived with Guillermo, but they weren’t related nor were they involved in any kind of standard relationship. In fact, the only thing most people knew about the arrangement was that, at some point, Consuelo had saved Guillermo’s life and the two had been together ever since. Their living together was not something people really cared all that much about and there was no reason to think about it too hard. Guillermo was the boss, if you didn’t count his brother, who ran everything from a shiny office in Dallas, where he pretended to be a legit businessman.

Regardless of what they were to each other, Consuelo meant the world to me. After meeting her for the first time at Guillermo’s house, she asked me to co

me back and see her for a limpia and a talk. I had no one else in Austin, so I waited a few days and showed up early.

Consuelo gave me the limpia and then offered me coffee. I ended up telling her everything about my life back in DF, how I ended up in trouble, and that I thought of myself as a coward for running to the US when things got ugly. Somehow I ended up crying while she held me and repeated, “Tranquilo, mijo, todo va a estar bien.”

After proving that I knew enough English to work wherever Guillermo decided to set me up, I had to drop by almost daily and give him a play-by-play of the previous night and hand him the money. I’m sure he did it to test me, to see if I was cutting into his cash or something. During these visits, I always ended up spending time with Consuelo. Those visits made me feel loved, welcome, cared for. Consuelo would always have a warm plate for me. Menudo. Pozole. Tamales. Pescado frito. Enchiladas rojas y verdes. Chilaquiles. Mole. Chiles en nogada con elotes frescos. Tacos al pastor. You name it, she could prepare it better than anyone.

The food was outstanding and the talks were even better. Consuelo quickly became my confidant, my guía espiritual, something like a madrecita and an abuela rolled into one. She was the first person I loved after leaving home, after feeling sad and lonely and like I would be sour and unhappy forever. She was the first person I really cared about after thinking I’d never care about anyone else ever again.

Consuelo era luz, era paz.

She was always what I needed and now I needed her more than ever.

4

Espíritus malos

Mexico es un monstruo

La luz – Warm egg – Dogs

That’s Ogún

Outside my window, the city went on as if nothing had happened. People jogged, ran around on their bikes, and walked their dogs. The brutality I’d seen the previous night belonged elsewhere. It belonged in Mexico. Except Indio’s eyes. Those belonged to a place that’s not a place, un lugar lleno de maldad. Remembering his eyes made me feel like la huesuda was running her thin, cold fingers down my back. I asked Santa Muerte for protection once more and thought about home.

Mexico es un monstruo. It devours people. It’s a dark place where bad things hide everywhere and evil people can be found around every corner. DF es una bestia gris that feeds on nine million souls every day. Los pinches gringos only care about what happens in la frontera because it’s close to them, they can smell la sangre y ver los muertos, but the beating heart of Mexico is DF, and it’s a black, polluted heart where bodies are found en las alcantarillas, girls are raped on buses in front of eyes that are only pretending to be blind, and people disappear without a trace way too often.

Mexico es una ciudad donde nadie es intocable.

Crazy as it sounds, I miss it. I left because someone was coming for me, and after five years away, now the same thing was happening. This time, I felt there was no place to run to. Austin was home. Don’t ask me how or why, but that’s how it felt.

Austin es diferente a Mexico, pero no demasiado. It has a nice face, but it’s as ugly as any other big city inside. There are young people walking the streets and too many damn parks and a lot of neon lights that seem to suck the danger out of the night air, so it’s easy to think nothing bad happens here. That’s wrong. Downtown Austin is full of junkies and East Austin is crawling with people who have been pushed into lives of crime because the university and the government and the never-ending list of tech companies keep bringing educated hijos de puta to town and they take all the jobs. And then there are people like Guillermo, a man who lives off the city’s vices como una remora gorda con bigote. This is a nice city the way New York is a nice city, which is to say that it only looks perfect if you don’t look too hard.

The drive to Guillermo’s house was quick. He lived on a short street near MoPac, the dividing line between los Mexicanos y negros del norte and the rich white folks of Westlake Hills.

I parked in front of his house and walked up to the door. Instead of knocking, which usually gets Consuelo’s pack of dogs howling, I sent Guillermo a text. He replied almost immediately, saying the door was open.

The house was a three-room, one-bathroom joint with a dirty beige carpet covering the living room floor. There was a huge brown L-shaped sofa a few feet from the door. In front of it sat a TV that was a few inches short of a movie theater screen. I’d never seen it turned on. Instead, Guillermo always hung out in the second room on the right.

As expected, I could see Consuelo in the kitchen, wearing one of her usual batas de noche, this one deep blue and full of red flowers. She smiled as I came in. I looked at her, smiled back. Sus cejas came together like two rams head-butting each other.

“Ay, mijo, estás rodeado de oscuridad!”

“Lo sé, tuve una mala noche.”

I kept my reply as cool as possible, but I knew she could read my soul. She could see the thing following me around like one of those black clouds en los muñequitos.

“Come, Fernando, come,” she said, waving me over.

I walked to the kitchen. Consuelo was waiting for me with her arms open, her six dogs standing next to her legs. I walked into her hug, bending over a little, and placed my head on her shoulder. She smelled of great food and that particular abuela smell that penetrates right down to your soul and makes you feel like a kid. Consuelo caressed my head and for a second I felt like I could take a nap right there, that no one could ever harm me in any way and that all bad thoughts would leave me, pushed away by the softness and warmth of her arms. Then she let me go, stepped back, caught her breath, and pulled out a chair for me. She signaled for me to sit and moved toward the fridge. The dogs followed her like they were tied to her short legs with a very short leash.

Consuelo closed the fridge’s door and turned around. She had an egg in her right hand.

“You don’t have to tell me what happened to you, but at least let me give you a limpia, mijito. It’ll help. Te lo aseguro.”

“You know Nestor?”

“¿El muchacho que trabajaba contigo?”

“Ese mismo.”

“What happened to him? Did he do something to you?”

“No, Nestor won’t be doing much of anything any more. Lo mataron anoche. Yo estaba allí cuando paso.”

“¿Quién lo mató?”

“I don’t know. Unos pinches mareros. De la Salvatrucha. Bad guys. They had a message for Guillermo. That’s why I’m here.”

“Watching someone die is a bad thing, Fernando, su fantasma se puede pegar a ti, pedir que lo vengues. Eso es una responsabilidad muy, muy grande. But a simple ghost doesn’t explain what I see around you. This thing you’re dragging around is heavier. It’s sharp. Peligrosa. I don’t like it. Tienes que sacarte de emcima lo que sea que agarraste anoche, mijo. No se puede andar así por la vida.”

One of Consuelo’s dogs let out a yelp that seemed to echo the old woman’s feelings. I looked down at the chingo. It looked back at me with eyes that spoke of more intelligence than those of half the people I had to talk to every night.

“El hombre que lo hizo, un tal Indio…he had black eyes. Y muchos tatuajes que…I don’t know, I think I saw them move. He also made a weird prayer as he killed Nestor, something about Ogún. No era español. It was something else. It made me feel cold. I was scared, Consuelo. I still am.”

Consuelo looked at me. Telling her I was scared was my way of asking her for protection. She was the kind of woman you can’t lie to because she can see through you, her eyes never getting stuck on the veil. She came toward me. Her dogs followed. The one she’d had the longest, a black and brown mutt she called Kahlúa, looked at me and whimpered. I looked at her and, for the millionth time, thought that dog had human eyes and a brain to match. Consuelo’s dogs weren’t violent, but they scared me because they seemed to understand everything that went on around them. They seemed to communicate with Consuelo without language and acted as if they understood every word that came out of anyone’s mouth.

Consuelo placed

her hand on my shoulder and I took my eyes off the chingos.

“Ogún is the god of iron and war. He is a very violent god. The man who killed Nestor was probably praying to him, offering Nestor’s blood as sacrifice. Elegguá opens the roads, but it is Ogún that clears the roads with his powerful machete. Los hijos de Ogún wear green and black necklaces and they pray to him whenever they take a life. Ogún oko dara obaniché aguanile ichegún iré. The prayer is to make sure that Ogún accepts the sacrifice, that the spilling of blood pleases him. It helps the killer keep los espíritus vengativos away. The prayer is a way of not having to deal with the anger and bad energy caused by a murder. Las vibraciones que dejan los muertos son una cosa muy, muy poderosa, Fernando. Ogún himself isn’t too bad when those praying to him are gente Buena, gente que tiene el alma pura. He’s the protector of metal workers. However, he’s also the god violent soldiers pray to, and it sounds like this man is one of those, mijo, un asesino.”

“Nando, get your ass in here!”

Guillermo’s voice put an end to Consuelo’s words. She looked toward the hallway and shook her head.

“Go and see him ahora, mijito. Tell him what’s going on. These men are crazy. Guillermo has dealt with planty of crazy men before and he will know what to do now. When you’re done with him, come back here so I can give you that limpia and a novena para que reces estos días. De verdad necesitas ambas cosas.”

I nodded and got up.

Guillermo was sitting on a brown recliner. A small TV sat atop a black coffee table in front of him. Two black ladies were screaming at each other onscreen. They waved their hands around, each full of nails so long they could probably scratch the back of their skulls every time they dug for a moco. Their screams mixed with the music coming from a boom box on the floor next to Guillermo’s chair. Algo con mucho acordeón y una voz chillona. As always, that combination took me back to that long ride in a stinky van with a quiet coyote. Why Guillermo had a TV and a radio always going at once was something I never understood. In the right corner of the room, below the room’s only window, was a second chair with an old blue guayabera draped over it. The shirt, according to Guillermo, had once belonged to Niño Fidencio. He’d paid $200 en un Mercado de pulgas for it. Underneath the chair, a candle with Niño Fidencio’s face on it burned. Guillermo didn’t leave his house much, but he somehow managed to always have a supply of candles at hand. Next to the chair was a stuffed gallo de pelea. His feathers were puffed out and his beak was open. It looked like it could give the bravest kid in the neighborhood the worst pesadillas he ever had.

Both Sides

Both Sides Hungry Darkness: A Deep Sea Thriller

Hungry Darkness: A Deep Sea Thriller Gutmouth

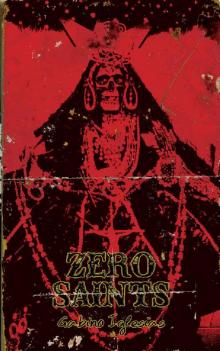

Gutmouth Zero Saints

Zero Saints